10.28.2006

10.26.2006

10.25.2006

The Site...

union machine works

2nd and clay st, oakland

saying it out loud that this could/should be my site made me more unsure about it than ever. so i went back today. it's all boarded up now, in preparation for its conversion to a whole foods. i found this discouraging, although ahmed suggests that perhaps integrating with the whole foods is the way to make the project financially viable. do these things matter in an architecture thesis? i know they do in my project, i want a program that includes a legit business, and real estate and education model. trying to best serve one of these goals will probably damage the other.

this pair of buildings are beautiful and historic and neglected. they sit in a neighborhood that is on the upswing, nearing crtical mass. on the same street lie key artist-run galleries and venues such as pro arts, swarm gallery and oakland metro. one building provides an open framework with wonderful light, which could be infilled with studios. the longer building is a stark, industrial hallway, like the tate, a public gallery that can help open up the block.

my thesis can constitute a counterproposal, for what the neighborhood could be if oakland publicly support the arts there instead continuing to treat area like an outdoor mall. either way will it simply be a catalyst for yuppies and the cultural elite to take over and make it their own, or will it do something for real place. and what is that place, jack london square, anyways?

is there somewhere in the city where this project can do more? will choosing a site that is more appropriate and within the means of my proposed program, will i end up disspointed with the architecture?

10.24.2006

Infrastructure as Instrument

T H E S I S F R A M E W O R K

Domain: position within the discourse

At its most basic level, urban design theory divides into utopian and natural models. The former relies on comprehensive vision and revision while the latter promotes incremental growth and gradual change. Architects must stake their authorship in the spectrum, and this study asserts that infrastructure is the tool for balancing top-down with bottom-up. Infrastructural operations offer large-scale design methodologies that exchange architects’ signature-making egos for leading roles in complex, collaborative place-making processes. By harnessing infrastructure’s design potential, architects can assume a more active and effective place among planners, developers, and other agents of urban change. Infrastructural architecture presents a conceptual framework for open-ended inter-scalar design, as advocated by contemporary architectural theorists and practitioners such as Stan Allen, Jesse Reiser, MVRDV, and FOA. These architects in turn follow the legacy of (among others) the Metabolists, Archigram, Archizoom, Superstudio, the Smithsons, and the Situationists.

Currently, spatially significant infrastructural elements belong to—or can be broken up into—one of two generic components, termed by Stan Allen corridor and patch. Corridor refers to a linear configuration, ranging in scale from The High Line to the

Objectives: goals / intents / questions

One fundamental urban question is primary for this thesis: how does an architect give space to the active unfolding of urban life without abrogating his responsibility to provide some form of order? In my proposal, I use infrastructure as a mediating force to concede and embrace an operative realism regarding architects’ design control. My intent is not to define specified functions, but to charge a field wherein a range of possible events might take place. Infrastructure operates in the continuum between utopian conception and dystopian response. Evading pro- and anti- rhetoric, it suspends judgment and tunes itself to forces at work in the urban environment.

My proposal coordinates urban forces, activating its context to produce a range of overlaps, adjacencies, and simultaneities. Its open webs condense and recalibrate patterns of urban life. Internal connections govern my proposal more than by any global figure. Porously interconnected, nodes and transitional spaces form a fabric of variable space.

10.23.2006

Gold v. Oil

Gold is so ‘90s, eh…I guess I will already have to start defending my thesis…

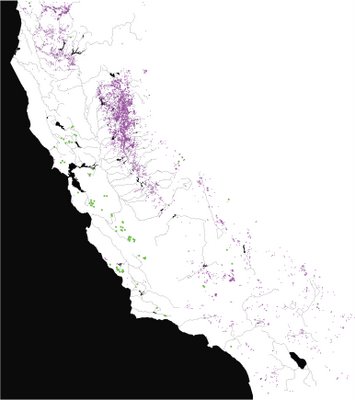

I like the reference to shale and oil, because it speaks directly to the issue that I am really trying to address: how and to what capacity do we value our land. The type of architecture we build speaks to this. The leaching of oil and pollutants is so ‘90s; I do not wish to simply make people see the damage we have done via maps (although I did draw one) or are doing. Rather, I think designing an architecture that is about coming to terms with our land is more progressive. Oil is deader than dead; anyone who believes there is a long-term future is envisioning a future I don’t want to see. But gold—its capacity as a capacitor gives it great promise in our digital milieu. Not the yellow wedding bands or dental grills, but in the purple Intel Core 2 Duo microchips and satellite transistors soon to be space-junk. All farmed here in Central Valley.

Purple is the new gold. It represents a new way of valuing the land. It is about building with the processes of the land that sustains our needs for processors. It is an attitude, reflected in the architecture, one that binds the architecture to the history and potential of the land, rather than expedient greed.

10.22.2006

Revised Domain

This relationship is best examined on the fringes, between the undeveloped and the developed, the virgin and the spoiled. These are the places that attract both mining and tourism—California being the paragon example. The most sublime public landscapes of the Sierra Nevadas, marked by theatrical geysers and waterfalls, can still be purchased for five dollars an acre according to an 1872 Mining Law still in effect today. Reflecting how little our attitude towards the natural landscape has changed over the past century, this is not an isolated condition. The infamous search for gold that has left such a devastating ecological legacy for California, from mercury spills to the massacre of native people, is still a nascent condition in pristine environments, such as the Amazon in Brazil.

This thesis investigates a new relationship between landscape and architecture, synthetically intertwining the act of tourism and mining with land remediation. A new form of ecotourism, the site is no longer a pristine wilderness, but the tailings of a gold mine. Instead of conceiving of sustainability simply as improved mechanical systems, architecture actively engages itself in a process of remediation. For example, phytomining is combined with phytoremediation, simultaneously ridding the soil of both it’s contaminates and the gold, which may be used to pay for the process. Pioneered in 1998 by New Zealand Earth Scientist Christopher Anderson and confirmed in experiments, the soil of mining sites can be treated with naturally occurring chemicals to allow plants, whose leaves turn purple from the process (gold is purple rather than yellow in its nano particulate form), to remediate the land while yielding up to 14 ounces of gold (approximately $8,400) per acre. Architecture, too, is embedded in the process of remediation by both exposing the scars of the past as well as creating specific innovations. This constitutes a new attitude towards the American landscape; one where building is not an object within a site, but inextricably tied to the landscape, embedded within the processes of reconciliation. The result is a new way of experiencing our [un]natural landscape.

Dan's Domain: Making Space for Art in Architecture

The spatial, programmatic and material needs of artists will drive the project towards the design of a community arts center. This is a place that will allow a diverse network of artists from all over the city to come together at a centralized place. Its primary aim is to support arts practice and education. However if the program is to be self-sustaining, and truly give artists control over their space, then it must address issues of economics, real-estate and community involvement. The community will be centered on a large, open studio floor that gives the younger, less experienced artists studying there enough space to be comfortable but also puts them in close proximity with their peers, allowing them to establish relationships between themselves and their work, to share and learn from one another. Individual studios will also be provided for the experienced artists that serve as mentors to the young artists. While providing privacy and containment, they will not seek to impose the architect’s will on the artist. Rather they will be designed as flexible frameworks that allow the artist to shape the space according to his or her needs. A machine shop for wood and metal will support a sculpture studio and allow the building’s inhabitants to construct internal architecture, furniture, contraptions and exhibition walls. Rather than designing the building as a finished product, it will be a framework that the artist’s working there can add to as they see fit. A gallery space will give the center’s inhabitants the ability to transfer their work directly from the studio to the marketplace, transferring control of the display and sales of artwork back to the artist. Finally a gallery store will give the center a street level presence that promotes economic sustainability and provides a more direct means for sharing work with the public. The primary objective of this project is to establish a program that goes beyond the allotment of square footages towards a comprehensive strategy for economic, social, political and educational engagement with the surrounding city. Like any good school, this arts center exists to support its students and mentors, and to serve the surrounding community.

The arts have shaped the form and culture of the city throughout the history of civilization. In the past two decades, however, the arts have become one of the most powerful modes of redevelopment in cities across the world. This broad phenomenon includes top-down, institutionalized projects like the Bilbao Guggenheim or the Tate Modern in London. A more interesting phenomenon, however, is the gradual shift of neighborhoods like SOMA in San Francisco, SOHO in New York and Fort Point in Boston from industrial areas, to artist enclaves, to cultural centers for the elite. Thus far, artists have fueled this phenomenon without having any control over it, as they are usually evicted by landlords and developers once they have helped raise property values with their galleries and boutiques. The question remains of how can artists take control of this process of arts-based redevelopment so that they benefit directly from the changes rather than developers and real estate agents. Oakland is a city that is on the verge of this type of transformation. All over the city, in West Oakland, Downtown, Jack London Square and on Telegraph Ave, artist communities, schools and galleries have begun to reclaim abandoned and disused spaces to support new communities and give focus to existing ones. The spaces available to these types of groups are more often than not the remnants of the city’s industrial past. The decaying industrial infrastructure that once served the interests of war and capitalism can be revitalized to create spaces for making the art and the culture of the city.

Labels: dbackman