4.13.2007

4.12.2007

4.08.2007

3.09.2007

Collage

“The pieces of paper (those vehicles of colour) which Le Corbusier pasted to sheets of drawing paper have an essential function for this artist who chose building as his vocation: they structure space…The symbolic presence of these luminous blocks, solidly moored to the margins of the page or else distributed over the picture surface with a lively feeling for formal rhythms and chromatic reverberation, enables Le Corbusier to shift from one plane to another, to capture the mobility of the external world and bring it into the picture. From the tectonic tension animating the image, restraining extemporaneous impulses without altogether suppressing them, there arise certain of the fundamental architectural principles which Le Corbusier strove to concretize: the idea of contrasting solid and transparent walls, the notion of free circulation within a constructed space, unobstructed passage from up to down, front to back – as free as the way the eye slides from one point on the horizon to another”[1]

“The pieces of paper (those vehicles of colour) which Le Corbusier pasted to sheets of drawing paper have an essential function for this artist who chose building as his vocation: they structure space…The symbolic presence of these luminous blocks, solidly moored to the margins of the page or else distributed over the picture surface with a lively feeling for formal rhythms and chromatic reverberation, enables Le Corbusier to shift from one plane to another, to capture the mobility of the external world and bring it into the picture. From the tectonic tension animating the image, restraining extemporaneous impulses without altogether suppressing them, there arise certain of the fundamental architectural principles which Le Corbusier strove to concretize: the idea of contrasting solid and transparent walls, the notion of free circulation within a constructed space, unobstructed passage from up to down, front to back – as free as the way the eye slides from one point on the horizon to another”[1]Collage is a way of making space. From the beginning, collage has played a critical role in the development of this thesis project. Early on in the process, the relationship between my collages and the projected design work was ambiguous and disjointed. I wanted to maintain the independence of these two modes of creation and did not want to force the design to develop out of my decidedly arbitrary and automatic art-making or to put my art into the service of a more straightforward architectural design. I still maintain that in terms of practice, architecture does not equal art, and that this thesis is a design project in the service of art and artists rather than a work of art in itself. However, while the collages are still meant to stand on their own as individual works of art, the notion of collage as a process of making space that I have derived from this work can now be applied to the design conception and process. The building’s relationship to collage is based on process rather than representation. It is not a collage in itself, it becomes a collage through its inhabitation.

The radical program of this thesis calls for a flexible environment for making, a participatory structure that liberates young artists from the constraints of the classroom by allowing them to continually reshape the individual and collective spaces of the facility.

The architecture remains latent until the participant artists of the program activate it through artistic production, social interaction and architectural reconfiguration. Moveable walls and operable environmental controls are a key component of this design, yet in themselves they do not comprise a truly flexible architecture. Sanford Kwinter describes Toyo Ito’s design process for the Sendai Mediatheque “not as a system of actions committed upon matter but rather of actions that take place within it.”[2] While Ito’s projects deals with the ethereal world of digital media rather than the decidedly material world of art practice,the architecture of Artists for Humanity similarly exists to support the actions and interactions of its youth and mentor artists. Through production, aggregation and reconfiguration, a constantly transforming three dimensional collage will be generated, in which few of the pieces are ever glued down, where changing social dynamics, lighting conditions and stages of artistic incompleteness will compose the space.

Thus I am not suggesting that the architectural proposal will come to resemble one of the collages that I have displayed alongside my design drawings. The architecture of this thesis is more akin to the 12”x16” sheets of Arches Watercolor paper on which I have drawn a squared grid before painting and collaging found images onto its surfaces. Collage is a process of establishing relationships between diverse media. As I cut out complimentary images and add lines and zones of color, the composition is constantly registered against the rectangular constraints of the paper and the grid. “The grid is a skeleton waiting to be fleshed out. It is about hierarchy, the permanent frame is something upon which more mutable things are hung.”[3]The 8’x 8’ grid of this project provides for a systematic approach to structure, daylighting, services and flexibility. It is a baseline against which the action of the space can be registered. Its accommodation of these systems within horizontal layers allows for complete freedom in between. Within this framework, my personal approach to collage can be reintroduced as a method of imagining the various permutations of inhabitation. By focusing on the process of space-making through collage, a truly free and flexible architecture can be developed that is both shaped by and in service of artistic practice.

[1] Rodari, Florian. Collage: Pasted, Cut and Torn Papers. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. 1988. p. 126-127

[2] Kwinter, Sanford. The Sendai Solid. CASE: Toyo Ito – Sendai Mediatheque. Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2002. p. 29

[3] Fontein, Lucie. Reading Structure through the Frame. Perspecta 31. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000. p. 52

2.18.2007

2.08.2007

2.04.2007

Labels: forrest

1.29.2007

1.26.2007

1.25.2007

1.24.2007

Shuijing in Studio

To all: Nice to be back amongst and amidst you...

It was one of those moments, talking with Shuijing, here in graduate school from the capital of China . Always a sense of the distant place she comes from, even as she makes such an earnest effort to communicate. (To make things objective, share in common.) Late afternoon, ninth floor of Wurster Hall, wide bank of windows to the south, looking out over misty winter rooftops of Berkeley and Oakland, backlit by the sun. Beautiful light. Desks still unsettled--not yet inhabited--it's just the beginning of the term. A rucksack, computer gear, pile of books and notes. Shadow opening on concrete wall--the new seismic pour--a burnished gray expanse, maybe four-feet thick, heavily reinforced... and within, another shadow, someone you almost know...

We were sitting and talking about her project in Beijing--to bring old forms into a world made entirely new... Raking light on wall just beyond, and the one curious non-Bauhaus arch... Pulled out my cell-phone camera, another kind of eye--like the story by the assistant of Joseph Cornell--riding with him on a bus once, somewhere in Queens, he noticed Cornell looking out the window and up into the sky--broad daylight, but the moon, quite visible, high above...

Malakoff Diggins Section

Hundreds of millions of years ago, a massive chunk of earth, submerged under the sea, was thrust upward as another piece rammed under it. Water was unwittingly trapped in this process, heated to extremes under the intense pressure of the earth. During this process, all sorts of minerals were dissolved into the water: chlorine, fluorine, boron, sulphur, tellurium, silica, and gold. When there was a fissure between the two plates, the pressurized water would be released from the earth, leaving behind a crystallized vein of quartz, marbled with gold, as the minerals were released. Over time, the ancestors of our modern rivers eroded these veins, carrying with them the gold deposits along their riverbeds.

Eventually, immigrants discovered this eroded gold in the streambeds of these ancient river’s descendants—the modern Yuba and American Rivers. A few years later and hundreds of thousands of people more, all this placer gold (or gold deposited in streams by erosion) had been removed from the stream beds using a simple pan or Long Tom. When things stopped “panning out”, the new immigrants turned to more complex sources; they began to seek “pay dirt” in the quartz veins of the mother lode itself as well as the buried, ancient streambeds of the ancestral rivers. To efficiently mine these buried riverbeds, a new mining technique had to be invented: hydraulic mining. Channeling the water of the existing rivers, the immigrants used pressurized monitors to remove the silt of the ancestral rivers. As the silt and gravel was washed away, mercury was added to remove the tiny particles of gold, transforming the earth into toxic mine tailings. These tailings were washed back into the present river systems, chocking the natural flow of water. The short-term removal of millions of years of sedimentation left devastating ecological consequence; little could grow in the newly exposed gravel, and what could grow was forced to exist in toxic levels of mercury.

Between its inception in 1853 and it cessation in 1883, hydraulic mining removed 1.25 billion cubic yards of earth—more than eight times that of the Panama Canal. At Malakoff Diggins alone, around 50 million yards were washed downstream, chocking the Yuba River and creating devastating floods and mercury contamination downstream. This section shows the geological composition of the site. Before hydraulic mining, the ground was over 400’ higher; what you see here is an enormous pit.

1.22.2007

http://berkeley-2007-branner.blogspot.com/

Folks--I've got a blog up based on our glorious forum and it's linked up with Yuki and Ivan, if you want to keep tabs. Hope things are going well. I'm enjoying my time truly madly deeply.

Dispersion: Family, Identity, and the Delocalized Home

Where’s home? Usually an innocuous question, to some it is cause for consternation. To ease confusion, the question can be rephrased. Where do you live? Universally less ambiguous, this question can be answered with little hesitation. But why should there be a distinction between the two inquiries?

Home connotes a single geographical space. City, region, and country are often called upon to describe the condition of Home. Associations tied to place are privileged and often dominate meanings of Home. Furthermore, the idea of Home is coupled with the idea of family. Home is the territory where family is defined.

The geographic fragmentation of family is a common contemporary condition. The dispersed family often requires a reinterpretation of Home. Thus, my thesis proposes to investigate the meaning of Home as the territory in which the shared identity of the geographically dispersed family is constructed.

In this investigation, I will draw upon personal ideas of Home and family. Although personally relevant, conditions of fragmentation, asynchronicity, plurality, and dispersion are also representative of a general postmodern reality. In assessing an alternate nature of Home, I will consider globalizing trends including increased personal mobility and electronic communication, multiple sites of habitation, and wider social and infrastructural networks. As local spatial conditions dissolve or become blurred, temporal coordinates are elevated to emphasize and anchor the meaning of Home.

In trying to reformulate the idea of Home, I will be examining my own family and the ways we negotiate family identity despite geographic separation. I will characterize how we communicate, forms of interaction, and our routines. As an alternative to place-centered definitions of Home, I have begun to envision Home as a kind of geographically dispersed infrastructure facilitating familial interactions, traditions, and rituals usually carried out in a typical home. In doing so, I will be exploring Home not through the redesign of a house, but through multiple (probably small-scale) architectural interventions that will involve existing infrastructure, institutions, and networks.

In envisioning Home as an infrastructure for the negotiation of family identity, I will begin by considering the synthesis of the supermarket and the automobile. Providing, respectively, for the modern necessities of sustenance and commuting, they represent a link to domesticity. As a context for daily life, these institutions are ubiquitous locally, nationally, and internationally. By considering these institutions as a departure point, I emphasize the prosaic aspects of domesticity in the construction and negotiation of family identity.

Home connotes a single geographical space. City, region, and country are often called upon to describe the condition of Home. Associations tied to place are privileged and often dominate meanings of Home. Furthermore, the idea of Home is coupled with the idea of family. Home is the territory where family is defined.

The geographic fragmentation of family is a common contemporary condition. The dispersed family often requires a reinterpretation of Home. Thus, my thesis proposes to investigate the meaning of Home as the territory in which the shared identity of the geographically dispersed family is constructed.

In this investigation, I will draw upon personal ideas of Home and family. Although personally relevant, conditions of fragmentation, asynchronicity, plurality, and dispersion are also representative of a general postmodern reality. In assessing an alternate nature of Home, I will consider globalizing trends including increased personal mobility and electronic communication, multiple sites of habitation, and wider social and infrastructural networks. As local spatial conditions dissolve or become blurred, temporal coordinates are elevated to emphasize and anchor the meaning of Home.

In trying to reformulate the idea of Home, I will be examining my own family and the ways we negotiate family identity despite geographic separation. I will characterize how we communicate, forms of interaction, and our routines. As an alternative to place-centered definitions of Home, I have begun to envision Home as a kind of geographically dispersed infrastructure facilitating familial interactions, traditions, and rituals usually carried out in a typical home. In doing so, I will be exploring Home not through the redesign of a house, but through multiple (probably small-scale) architectural interventions that will involve existing infrastructure, institutions, and networks.

In envisioning Home as an infrastructure for the negotiation of family identity, I will begin by considering the synthesis of the supermarket and the automobile. Providing, respectively, for the modern necessities of sustenance and commuting, they represent a link to domesticity. As a context for daily life, these institutions are ubiquitous locally, nationally, and internationally. By considering these institutions as a departure point, I emphasize the prosaic aspects of domesticity in the construction and negotiation of family identity.

Making Space (Dan)

The life and work of the artist is intricately tied to the space in which he or she practices. Understanding the space of the artist at multiple levels of experience is essential to the development of the program and the architecture of this thesis. The studio is a personal and private space, organized and continually reconfigured to suit the individual artist’s needs. Yet while the individual artist has the right and perhaps the duty to express themselves as such, the work of the artist is most meaningful when it is part of the shaping of a collective spirit or vision amongst these diverse individuals. Thus the studio is understood not as a site of isolation but of community. Communities of artists can in turn use their vision to participate in and possibly transform the culture of the city in which they practice. Many artists communities thrive in the Bay Area, but for high school students in urban schools who often feel disenfranchised and voiceless within the confines of classroom and who might have limited opportunities to make art, the provision of a space in which they can be themselves, learning and making in an environment where they feel comfortable, can be life-changing.

My thesis project will define educational, operational and spatial program for a distinctive arts program tentatively called the Bay Area Youth Artists for Humanity (BayAFH). Developed in collaboration with an existing program in Boston which began in 1991, it will bring together Bay Area high school students and practicing artists to produce artwork for practice, exhibition and sale. I will propose a visionary design to house BayAFH on a group open lots at 4th and Washington Streets in the Jack London District of Oakland. The design will reflect the philosophy and long-term goals of the program rather than a smaller, more realistic, approach to providing space for BayAFH in the immediate future. It will promote a positive, dynamic relationship between the individual participants, between the working artist and the youthful artist in the process of becoming; between BayAFH artists and the immediate community; and between all of these players and the larger cultural life of the city. My thesis tries to establish a model for a community art center whose programs and physical assets could establish it as a permanent feature of a reviving neighborhood, protecting it from being pushed aside in the gentrification process, and instead embracing and leading the coming change. A new model for community based art education is needed to insure relevance, accessibility and viability. In order to empower Oakland’s youth through art, they must be able to express themselves through both physical artifacts and a social involvement with each other, their mentors, and the community.

This is an architecture at the service of artists, and the design aims to establish a more dynamic and reciprocal relationship between architectural and art practice, education and exhibition. Rather than designing the building as a finished product, it will be a framework that the inhabitants can transform and augment as they see fit. The design process will unfold through the investigation of four principle criteria of flexibility, sustainability, light and fun.

My thesis project will define educational, operational and spatial program for a distinctive arts program tentatively called the Bay Area Youth Artists for Humanity (BayAFH). Developed in collaboration with an existing program in Boston which began in 1991, it will bring together Bay Area high school students and practicing artists to produce artwork for practice, exhibition and sale. I will propose a visionary design to house BayAFH on a group open lots at 4th and Washington Streets in the Jack London District of Oakland. The design will reflect the philosophy and long-term goals of the program rather than a smaller, more realistic, approach to providing space for BayAFH in the immediate future. It will promote a positive, dynamic relationship between the individual participants, between the working artist and the youthful artist in the process of becoming; between BayAFH artists and the immediate community; and between all of these players and the larger cultural life of the city. My thesis tries to establish a model for a community art center whose programs and physical assets could establish it as a permanent feature of a reviving neighborhood, protecting it from being pushed aside in the gentrification process, and instead embracing and leading the coming change. A new model for community based art education is needed to insure relevance, accessibility and viability. In order to empower Oakland’s youth through art, they must be able to express themselves through both physical artifacts and a social involvement with each other, their mentors, and the community.

This is an architecture at the service of artists, and the design aims to establish a more dynamic and reciprocal relationship between architectural and art practice, education and exhibition. Rather than designing the building as a finished product, it will be a framework that the inhabitants can transform and augment as they see fit. The design process will unfold through the investigation of four principle criteria of flexibility, sustainability, light and fun.

Labels: dbackman

1.11.2007

1.08.2007

12.26.2006

12.20.2006

Death by Freeway

If the angel of history is propelled into the future by the storm of progress, then this storm is most certainly stirred by desire. This desire is a complicated subject, its objects being both the conservative nostalgia of reconstructing the past and the radical utopianism of constructing the future. The present is continuously deconstructed, perceivable only in fragments of vague images. In our attempts to piece them together the immediacy of want betrays the bipolar temporality of desire, that abrasive symbiosis of hope and regret, while the fertile yet one-dimensional collective mind produces of what it is only geometrically capable (chronology).

The aggressive and unyielding vectors of causality cut through the city unrelentingly. The anonymity of the grid is freedom. Comfortably coddled by his mobile psychological infrastructure, the iPod-toting hipster becomes a stoic simulacrum of his more vibrant silhouette. The arteries of the city, lifted as if to meet him, peel away from the valley’s floor and commence the aerial tangle. The automobile, like the progress that it so singularly symbolizes, is fluidly transferred while down below the cells, betrayed, coagulate in the shadows. Trapped as we are in these cells (willingly or not – it is unclear), where the ossifying joints of memory seize us upon our nostalgic trajectory toward utopia’s monolithic asymptote, should we push forward in directions unknown or do we risk desiring nothing more than to meekly tend the glass menagerie?

In the ancient Greek cities the dead were buried in the necropolis, just outside the city walls. This practice both allowed the citizens to use the space within the city walls more effectively and potentially observe prohibitions on burial within the city limits. In the American metropolis today, the city limit is no longer the boundary of inhabitation and hasn’t been for some time. The complete domination of suburban sprawl as the model for American city growth since the 1950s means that the dead buried outside the city limits in the 20th century are now the occupants of new suburban city limits. Colma, California, for instance, is a sprawling landscape of the dead located south of San Francisco and serving as its neighbors burial grounds since the early 1900s when the city passed an ordinance outlawing cemeteries within its limits. Colma now has its own BART station.

The desire to remember the dead is dissociated from their physical remains. The bucolic cemetery landscape is a bloated leach in the urban fabric. The paradigm of grave stone architecture territorializes a space and a program that should be a communal space of collective memory. Likewise, we turn our collective mind away from the space beneath the urban infrastructure. The soaring concrete highway overpass is a beautiful, lonely behemoth. I propose to regard the space beneath the freeway as a collective space of memory and desire dislocated from the temporality of being and the linear domination of the automobile.

The act of making is inescapably a process of layering, but the art of making – to borrow Calvino’s words – is “the sudden agile leap of the poet-philosopher who raises himself above the weight of the world, showing that with all his gravity he has the secret of lightness, and that what many consider to be the vitality of the times – noisy, aggressive, revving and roaring – belongs to the realm of death, like a cemetery for rusty old cars.” As during the first industrial revolution when we carved a space in our hearts for the hand crafted, we must now make room for an even more perverse nostalgia – that of the mass-produced monolith. The subject here is the representation of that which is slipping away and only momentarily captured by words. My initial study is to understand what is revealed and what is occluded by the detritus of making.

The aggressive and unyielding vectors of causality cut through the city unrelentingly. The anonymity of the grid is freedom. Comfortably coddled by his mobile psychological infrastructure, the iPod-toting hipster becomes a stoic simulacrum of his more vibrant silhouette. The arteries of the city, lifted as if to meet him, peel away from the valley’s floor and commence the aerial tangle. The automobile, like the progress that it so singularly symbolizes, is fluidly transferred while down below the cells, betrayed, coagulate in the shadows. Trapped as we are in these cells (willingly or not – it is unclear), where the ossifying joints of memory seize us upon our nostalgic trajectory toward utopia’s monolithic asymptote, should we push forward in directions unknown or do we risk desiring nothing more than to meekly tend the glass menagerie?

In the ancient Greek cities the dead were buried in the necropolis, just outside the city walls. This practice both allowed the citizens to use the space within the city walls more effectively and potentially observe prohibitions on burial within the city limits. In the American metropolis today, the city limit is no longer the boundary of inhabitation and hasn’t been for some time. The complete domination of suburban sprawl as the model for American city growth since the 1950s means that the dead buried outside the city limits in the 20th century are now the occupants of new suburban city limits. Colma, California, for instance, is a sprawling landscape of the dead located south of San Francisco and serving as its neighbors burial grounds since the early 1900s when the city passed an ordinance outlawing cemeteries within its limits. Colma now has its own BART station.

The desire to remember the dead is dissociated from their physical remains. The bucolic cemetery landscape is a bloated leach in the urban fabric. The paradigm of grave stone architecture territorializes a space and a program that should be a communal space of collective memory. Likewise, we turn our collective mind away from the space beneath the urban infrastructure. The soaring concrete highway overpass is a beautiful, lonely behemoth. I propose to regard the space beneath the freeway as a collective space of memory and desire dislocated from the temporality of being and the linear domination of the automobile.

The act of making is inescapably a process of layering, but the art of making – to borrow Calvino’s words – is “the sudden agile leap of the poet-philosopher who raises himself above the weight of the world, showing that with all his gravity he has the secret of lightness, and that what many consider to be the vitality of the times – noisy, aggressive, revving and roaring – belongs to the realm of death, like a cemetery for rusty old cars.” As during the first industrial revolution when we carved a space in our hearts for the hand crafted, we must now make room for an even more perverse nostalgia – that of the mass-produced monolith. The subject here is the representation of that which is slipping away and only momentarily captured by words. My initial study is to understand what is revealed and what is occluded by the detritus of making.

12.14.2006

12.04.2006

At last. Keehyun's domain But need more...infinitely...

Queer Constellation in architecture

In recent years, the increasing cultural representation of homosexual concerns and the recent queering of sex-gender identities undoubtedly have effect on urban lifestyle and context. If we look for examples of Queer space, that will be AIDS memorial Quilt, gay village, and certain kinds of public space -- parks, bars and baths. Within the range of subtle social and aesthetic amenities important to service economies, Queer space is one of several competing designing paradigms based on recognition of “difference.” But, so far, queer space is something that is not built, only implied, and usually invisible. Queer space does not confidently establish a clear, ordered space for itself.

Meanwhile, according to Queer Theory, “Queer” embraces a proliferation of sexualities (bisexual, transgender, pre and post-op transsexual) and the compounding of outcast positions along racial, ethnic, and class, as well as sexual lines. In other words, Queer not only troubles the gender asymmetry implied by the phrase “lesbian and gay,” but potentially includes “deviant” and “perverts” why may traverse or confuse hetero-homo division and exceed or complicate conventional delineations of sexual identity and normative sexual practice.

Considering all this respect, I will reconsider architecture’s fundamental regions for deprogramming space. In our society, we have conventionalized and stabilized ritual in acting, whether formally (onstage) or in the street. Likewise, architecture has been concerned with norms as well: with the design of forms and images that aspire to universal and conventional appeal. Architecture has often been employed to “stabilize” or “standardize” social context, rather than to spark creative forms of social change. But I think gay experience and queer-scape architecture, especially when based on modified forms of queer theory, can have the diverse effect.

Queer space will be proposed as different scene in urban area, that functions as a “counterarchitecture”, ‘appropriating, deprogramming, mirroring, and choreographing’ mundane everyday life. I do not mean to imply that only homosexuality can impose new, abstract nature, or that it is the only way to escape from the stricture of our building. But I believe that queer space, because of the certain role we have assigned homosexuality within our society, can afford a certain archetype for deprogrammized architecture. No matter what the sexual preferences of the persons make queer space or use it, I will believe queer space can set up the new way of architectural construction that can subvert existent one.

In terms of the purpose of building, I tried to make space for queers or queers sexuality. It will become community center because there is no specific building to serve visible and powerful queer culture. But, I will be cautious about generating contradiction: that is making architecture for queers is very easy to make segregation from the people, and that is very controversial from Queer theory. The issue is how to dissolve the interference between the sexual preference and complex and controversial philosophy or social network. Furthermore, It will contain diverse activity having mutable, fluid terrain (rather than plate). It could be architectural experiment with miscellaneous spatial species.

Repeatedly, what I am trying to construct by exploring the topic of queer space is not, primarily, an interest in gay culture but a fascination with the idea of the “counterarchitecture” mirroring, deprogramming, and choreographing’ mundane everyday life.

In recent years, the increasing cultural representation of homosexual concerns and the recent queering of sex-gender identities undoubtedly have effect on urban lifestyle and context. If we look for examples of Queer space, that will be AIDS memorial Quilt, gay village, and certain kinds of public space -- parks, bars and baths. Within the range of subtle social and aesthetic amenities important to service economies, Queer space is one of several competing designing paradigms based on recognition of “difference.” But, so far, queer space is something that is not built, only implied, and usually invisible. Queer space does not confidently establish a clear, ordered space for itself.

Meanwhile, according to Queer Theory, “Queer” embraces a proliferation of sexualities (bisexual, transgender, pre and post-op transsexual) and the compounding of outcast positions along racial, ethnic, and class, as well as sexual lines. In other words, Queer not only troubles the gender asymmetry implied by the phrase “lesbian and gay,” but potentially includes “deviant” and “perverts” why may traverse or confuse hetero-homo division and exceed or complicate conventional delineations of sexual identity and normative sexual practice.

Considering all this respect, I will reconsider architecture’s fundamental regions for deprogramming space. In our society, we have conventionalized and stabilized ritual in acting, whether formally (onstage) or in the street. Likewise, architecture has been concerned with norms as well: with the design of forms and images that aspire to universal and conventional appeal. Architecture has often been employed to “stabilize” or “standardize” social context, rather than to spark creative forms of social change. But I think gay experience and queer-scape architecture, especially when based on modified forms of queer theory, can have the diverse effect.

Queer space will be proposed as different scene in urban area, that functions as a “counterarchitecture”, ‘appropriating, deprogramming, mirroring, and choreographing’ mundane everyday life. I do not mean to imply that only homosexuality can impose new, abstract nature, or that it is the only way to escape from the stricture of our building. But I believe that queer space, because of the certain role we have assigned homosexuality within our society, can afford a certain archetype for deprogrammized architecture. No matter what the sexual preferences of the persons make queer space or use it, I will believe queer space can set up the new way of architectural construction that can subvert existent one.

In terms of the purpose of building, I tried to make space for queers or queers sexuality. It will become community center because there is no specific building to serve visible and powerful queer culture. But, I will be cautious about generating contradiction: that is making architecture for queers is very easy to make segregation from the people, and that is very controversial from Queer theory. The issue is how to dissolve the interference between the sexual preference and complex and controversial philosophy or social network. Furthermore, It will contain diverse activity having mutable, fluid terrain (rather than plate). It could be architectural experiment with miscellaneous spatial species.

Repeatedly, what I am trying to construct by exploring the topic of queer space is not, primarily, an interest in gay culture but a fascination with the idea of the “counterarchitecture” mirroring, deprogramming, and choreographing’ mundane everyday life.

Queries and Plans

The individual talks with each of you were productive--and enjoyable. I think we left it that there WOULD be a class meeting tonight, same time, same place (170 at 7:00). Let's get together there, at least for an hour, to see where everyone's at, and how to proceed...

12.03.2006

Angels Camp

Mining country--along old Highway 49. The goldrush towns--Murphy, Volcano, Mokelumne Hill, brick buildings of imported stature, a Boston cornice, Concord arch--sluices and shutes, all still visible along the higher roads, hillsides giving way to slag, now overgrown, buried, waiting to be reclaimed. The color purple--royalty in ancient times, and beyond--maybe the most artificial of tones, never quite red, never quite blue, but fitting, somehow, as a repository of planted hope. Let it grow over, refurbish, return to earth...

12.02.2006

11.29.2006

W.G. Clark

"There was a mill near my home town. It was a tall timber structure on a stone and concrete base which held the water wheel and extended to form the dam. One did not regret its beings there, because it made more than itself; it made a millpond and a waterfall, creating at once stillness and velocity; it made reflections and sound. There was an unforgettable alliance of land to pond to dam to abutment to building. It was not a building simply imposed on a place; it became the place, and thereby deserved its being—an elegant offering paid for the use of the stream." --from his essay "Replacement"

Site Proposal

This thesis proposes a site at the intersection of 4th and Washington St. in Oakland, California for the design a new facility to house the envisioned Bay Area Youth Artists for Humanity program. The site is composed of three parcels, currently occupied by a three individual parking lots, two privately and one public. The corner lot, at 409 Washington Street, occupies 7050 square feet and the middle lot, at 518 4th St, occupies 4583 square feet. Both are rectangular sites. The third lot does not have any information readily available about it. It is nearly equal in area, but is roughly triangular in shape, tapering down to just 15 feet wide at the western boundary. All three lots are asphalt paved and surrounded by chain link fence and contain no built structures. In addition, a narrow strip of land tapers off along 4th Street to the east of the second lot, providing a 10 foot buffer between the sidewalk and the BART fence. This parcel would not be built upon but would be included in the landscaping plan.

The site is a residue of open space leftover by the construction of the city’s transportation infrastructure. The tunnel exit/entrance for BART bounds the north side, a deep trench which holds eastbound and westbound subway lines, between concrete retaining walls. One block further north is the merge point for the 880 and 980 freeways. Two blocks south runs the Amtrak and freight rail lines. Beyond that is the Oakland Estuary a shipping channel between Oakland and Alameda that serves the port infrastructure to the west.

Hemmed in by infrastructure, the site sits at a crossroads within Oakland. This neighborhood is well-served by all modes of urban transportation, including bus, subway, train, car and ferry, and yet it is cut off from the center of the city by the linear arrangement of these lines. This condition allowed the conversion of the neighborhood from industrial to commercial and residential to occur, but remains a burden to the area in terms of its physical presence. This industrial/seaport/transportation nexus condition is held in common with many other recently redeveloped areas in the country, such as SOMA in San Francisco, Fort Point in Boston, the Meatpacking District in New York. In all these cases, the confluence of infrastructure facilitated industrial uses, but as this infrastructure was upgraded in the post-war years, the fabric of the neighborhood was torn apart. In these situations, the influx of arts and culture have been a prime means for revitalizing the area. The City of Oakland is cognizant of these factors and has put in much effort to use them to its advantage.

Currently, the area is defined by Jack London Square, a 1970’s mixed-use redevelopment that contains hotels, restaurants, retail and office space. The square was perhaps a good idea in terms of planning but was constructed in an architectural language that is tacky and dated. The square is a prime tourist destination for Oakland but has had much difficulty attracting city residents and has seen many of its retail tenants depart in recent years. The larger area around the square, now called the Jack London District, is a former industrial warehouse zone that now holds a variety of businesses, largely in renovated warehouse spaces. The push for the redevelopment of the area is underway, as outlined in the Oakland Estuary Policy Plan. Many of the typical identifiers of gentrification, such as residential-loft conversions, design firms, and artists studios, can be found here. The plan, however, makes it clear that in this particular portion of the plan arts and cultural uses should be supported.

In the case of the artist spaces, however, there is an interesting trend in the Jack London District that differentiates it from other artist zones, like the one along Telegraph Ave. While the Art Murmur galleries of Telegraph bank on a claim to a geographically defined territory within the city (which brings with it all sorts of ethical questions) the galleries, performance spaces and studios of the Jack London District, take on a more inclusive identity the revolves around outreach to the city as a whole. Pro Arts Gallery is exemplary of this condition, as the program not only operates a gallery in the area, but organizes the East Bay Open Studios and serves a network of hundreds of artists across the whole region. While this approach does not neglect its surroundings, it looks beyond the notion of trying to fix or help a deserving place, towards serving a larger community.

This approach reveals a potential for the neighborhood to become a cultural crossroads for Oakland rather than just an infrastructural one. Bay Area Youth Artists for Humanity aims strives to become part of and strengthen this cultural context. The architectural proposal will become a site for a much larger network of youth and mentor artists, members, patrons and visitors who arrive there to learn, create and experience. Rather than seeking a singular context to relate to and trying to adapt to the specificity of a particular neighborhood, the program intends to create a new community whose locality is all of Oakland, in which diverse individuals from all over the city can come together. The program will celebrate and be shaped by the various gravitational forces that affect the area, from Downtown, Chinatown, Uptown, West Oakland, the Port, the Lake, Jingletown, Fruitvale, San Antonio and even Alameda. As a newcomer to Oakland, this situation is ideal for one who cannot claim a specific neighborhood but is more interested in interactions with a cross-section of the city’s inhabitants. The hope is that working alongside the other non-profit arts organizations in the area, such as Pro Arts Gallery, Swarm Studios, Oakland Metro, MOCHA, Oaklandish and the Crucible, the BayAFH can be part of a cultural transformation for this part of the city.

That said the quirky mix of uses in the neighborhood opens up many opportunities for involvement and cooperation for a young arts program. Other non-profits, like Sports for Kids, Pro Arts, and Oakland Metro make their homes here. Tourists who find little of the culture of Oakland contained in the square itself are eager to soak it up in the nearby galleries. Restaurants and bars provide some semblance of a night-life. A loose compound of civic and social services, including the Oakland Police Department, Courthouse, Social Welfare, Probation and directly across the street from the site, the City Coroner’s office. For better or worse, more and more lofts are popping up to the north and west, and with them the inevitable signs of gentrification. Above all this tower the cranes of Oakland’s port, reminding everyone that this remains as a working port zone despite its gradual conversion. This is a context that is transitional, conflicted and hard to pin down. This thesis proposes that BayAFH can be a unifying for the area, using art to simultaneously strengthen the existing community and create a new one.

After a lot of careful consideration I have decided to design on an open site from the ground up. While doing an adaptive reuse project had great appeal, this open site offers more potential, to do an innovative design project and to deal with the realities and limitations of the proposed situation. This thesis will propose a visionary design for the site that considers the ideal situation for the BayAFH program rather than the initial conditions. Programs like the one I have in mind never start big. They work their way up from humble beginnings. The original Artists for Humanity in Boston began when a practicing artist invited a group of six students to come work with her in her tiny studio. They spent two or three years there, learning to paint and completing only a few commissions before they found a suitable space. And when they found that space, it was essentially donated to them because the real estate owner was inspired by their vision. It is my intention to use this project to research spatial, programmatic, educational and economic tactics that support this particular design proposal and can also be carried with me as I attempt to actually impliment this program in the coming years.

Labels: dbackman

11.28.2006

Purple Gold: Architecture as an Act of Remediation

Abstract:

The extent to which construction changes the landscape is seldom considered. Although the word construction implies a positive formation, its beginnings are marked by destruction: land is cleared and reconfigured. Many of our values emerge in this process; landscapes become real estate and architecture is reduced to style, with the relationship between the two wholly discreet. The all too familiar result is rarely satisfying. To remedy this, building should be a synergistic action—one that offers new potentials where landscape, architecture and place are interwoven. This relationship is magnified on the fringes between the undeveloped and the developed, the virgin and the spoiled. In America, these places are diametrically claimed as resources, simultaneously qualifying as existential national treasures and mining rights valued at five dollars an acre. It is in these distinctly American landscapes, economically defined by tourism and mining, that new typologies for building within a landscape can be explored. The result is a new way of experiencing our [un]natural landscape

Statement of Purpose:

To investigate a new relationship between landscape and architecture, the act of tourism and mining are synthetically intertwined with land remediation. A new form of ecotourism is proposed where the site is no longer a pristine wilderness, but the tailings of a gold mine. Instead of conceiving of sustainability simply as improved mechanical systems, architecture actively participates in the process of remediation. For example, phytomining is combined with phytoremediation, using plants to simultaneously rid the soil of both contaminates and gold, the latter being used to pay for the process. Pioneered in 1998 by the New Zealand Earth Scientist Christopher Anderson and confirmed in experiments, the soil of mining can be treated with naturally occurring chemicals to allow the plants, whose leaves turn purple from the process (gold is purple in its nano particulate form), to absorb the metals. The plants rid the soil of both contaminates, such as mercury, and gold, yielding up to 14 ounces (approximately $8,400) per acre. Participation is ushered into the process through tourism, where visitors can involve themselves in the history of the land—both in learning the past abuses and actively bettering its future.

The American West is ripe with land spoiled by the dream of gold. The theatrical waterfalls and geysers that define so many of America’s national parks are next to some of the largest mining operations. The infamous search for gold and other minerals has left a devastating ecological legacy in the American West, from mercury spills to the massacre of native people. What is mostly a distant memory in states such as California is still a nascent condition in pristine environments, such as the Amazon in Brazil. In my research, I will seek to understand the cyclic nature of these places, examining recent mining explorations, their latent legacy on the environment, and how these places can be remediated through a built intervention.

Intellectual Context:

Throughout history, architecture has primarily been about object, iconography and meaning. Palladio’s Villa Rotunda, as shown in his Four Books on Architecture, is a pattern to be superimposed on any landscape. Its system of organization is entirely internalized and its geometry is pure and self-determined. A pedestal-like base elevates the piano nobile, separating building from ground. Modern tradition follows suit. Le Corbusier, evidenced in his five points, sought to reduce architecture to a kit of parts. The paradigmatic Villa Savoye’s pilotis suspend the building above the ground, creating a relationship between object and landscape similar to camera and subject: landscape is reduced to view. As such, architecture does not engage the landscape, but rather represents mans rise above it.

This reflects a larger attitude towards the land that has come to define architecture in America. Architecture is reduced to style and landscape becomes real estate. The disconnect manifests itself in both manicured lawns and brownfields. There are several architectural practices that are seeking to more intimately tie building to landscape, such as Reiser + Umemoto. The Alishan Tourist Resort seeks to intimately tie what is built into the landscape.

Problem Statement:

How can architecture be structured systemically so that it works synergistically with the landscape to better the condition of place?

Project Definition:

The project exists on land that, although it was once pristine, has been exploited by man. The value of the landscape has not been its holistic sense of place, but rather the discreet minerals found deep beneath it. The process of extraction has resulted in spoiled land—land where the act of digging, an essential element in architecture, has toxic consequences. The site represents the unsustainable attitude of manifest destiny that has characterized the American West: it is the tailings of a gold mine.

The project seeks to define new attitudes towards the land through an architectural proposal. Beginning with land remediation, strategies to reintroduce people into the landscapes they ruined are the ultimate goal. The program is multifaceted: it will remind of past transgressions (museum?), actively engage remediation (exploratorium?), and present new potentials (tourism?).

The extent to which construction changes the landscape is seldom considered. Although the word construction implies a positive formation, its beginnings are marked by destruction: land is cleared and reconfigured. Many of our values emerge in this process; landscapes become real estate and architecture is reduced to style, with the relationship between the two wholly discreet. The all too familiar result is rarely satisfying. To remedy this, building should be a synergistic action—one that offers new potentials where landscape, architecture and place are interwoven. This relationship is magnified on the fringes between the undeveloped and the developed, the virgin and the spoiled. In America, these places are diametrically claimed as resources, simultaneously qualifying as existential national treasures and mining rights valued at five dollars an acre. It is in these distinctly American landscapes, economically defined by tourism and mining, that new typologies for building within a landscape can be explored. The result is a new way of experiencing our [un]natural landscape

Statement of Purpose:

To investigate a new relationship between landscape and architecture, the act of tourism and mining are synthetically intertwined with land remediation. A new form of ecotourism is proposed where the site is no longer a pristine wilderness, but the tailings of a gold mine. Instead of conceiving of sustainability simply as improved mechanical systems, architecture actively participates in the process of remediation. For example, phytomining is combined with phytoremediation, using plants to simultaneously rid the soil of both contaminates and gold, the latter being used to pay for the process. Pioneered in 1998 by the New Zealand Earth Scientist Christopher Anderson and confirmed in experiments, the soil of mining can be treated with naturally occurring chemicals to allow the plants, whose leaves turn purple from the process (gold is purple in its nano particulate form), to absorb the metals. The plants rid the soil of both contaminates, such as mercury, and gold, yielding up to 14 ounces (approximately $8,400) per acre. Participation is ushered into the process through tourism, where visitors can involve themselves in the history of the land—both in learning the past abuses and actively bettering its future.

The American West is ripe with land spoiled by the dream of gold. The theatrical waterfalls and geysers that define so many of America’s national parks are next to some of the largest mining operations. The infamous search for gold and other minerals has left a devastating ecological legacy in the American West, from mercury spills to the massacre of native people. What is mostly a distant memory in states such as California is still a nascent condition in pristine environments, such as the Amazon in Brazil. In my research, I will seek to understand the cyclic nature of these places, examining recent mining explorations, their latent legacy on the environment, and how these places can be remediated through a built intervention.

Intellectual Context:

Throughout history, architecture has primarily been about object, iconography and meaning. Palladio’s Villa Rotunda, as shown in his Four Books on Architecture, is a pattern to be superimposed on any landscape. Its system of organization is entirely internalized and its geometry is pure and self-determined. A pedestal-like base elevates the piano nobile, separating building from ground. Modern tradition follows suit. Le Corbusier, evidenced in his five points, sought to reduce architecture to a kit of parts. The paradigmatic Villa Savoye’s pilotis suspend the building above the ground, creating a relationship between object and landscape similar to camera and subject: landscape is reduced to view. As such, architecture does not engage the landscape, but rather represents mans rise above it.

This reflects a larger attitude towards the land that has come to define architecture in America. Architecture is reduced to style and landscape becomes real estate. The disconnect manifests itself in both manicured lawns and brownfields. There are several architectural practices that are seeking to more intimately tie building to landscape, such as Reiser + Umemoto. The Alishan Tourist Resort seeks to intimately tie what is built into the landscape.

Problem Statement:

How can architecture be structured systemically so that it works synergistically with the landscape to better the condition of place?

Project Definition:

The project exists on land that, although it was once pristine, has been exploited by man. The value of the landscape has not been its holistic sense of place, but rather the discreet minerals found deep beneath it. The process of extraction has resulted in spoiled land—land where the act of digging, an essential element in architecture, has toxic consequences. The site represents the unsustainable attitude of manifest destiny that has characterized the American West: it is the tailings of a gold mine.

The project seeks to define new attitudes towards the land through an architectural proposal. Beginning with land remediation, strategies to reintroduce people into the landscapes they ruined are the ultimate goal. The program is multifaceted: it will remind of past transgressions (museum?), actively engage remediation (exploratorium?), and present new potentials (tourism?).

11.24.2006

Dispersion : Family, Identity, and the Delocalization of Home

Home connotes a single geographical space. City, region, and country are often called upon to describe the condition of Home. Associations tied to place are privileged and often dominate meanings of Home. Additionally, the idea of Home is coupled with the idea of family. Home is the territory where family is defined.

The geographic fragmentation of family is a common contemporary condition. The dispersed family often requires a reinterpretation of Home. My thesis proposes to investigate the meaning of Home as the territory in which the group identity of the geographically dispersed family is constructed.

In this investigation, I will draw upon personal ideas of Home and family. Although personally relevant, conditions of fragmentation, asynchronicity, plurality, and dispersion are also representative of a general post-modern reality. In assessing an alternate nature of Home, I will consider globalizing trends including increased personal mobility and electronic communication, multiple sites of habitation, and wider social and infrastructural networks. As local spatial conditions dissolve or become blurred, temporal coordinates are elevated to emphasize and anchor the meaning of Home.

The geographic fragmentation of family is a common contemporary condition. The dispersed family often requires a reinterpretation of Home. My thesis proposes to investigate the meaning of Home as the territory in which the group identity of the geographically dispersed family is constructed.

In this investigation, I will draw upon personal ideas of Home and family. Although personally relevant, conditions of fragmentation, asynchronicity, plurality, and dispersion are also representative of a general post-modern reality. In assessing an alternate nature of Home, I will consider globalizing trends including increased personal mobility and electronic communication, multiple sites of habitation, and wider social and infrastructural networks. As local spatial conditions dissolve or become blurred, temporal coordinates are elevated to emphasize and anchor the meaning of Home.

11.21.2006

The Program: Bay Area Youth Artists for Humanity

The goal of this thesis, Making Space for Art in Architecture, is the development of a unique program, which supports a new form of artist community in the city of Oakland, California. This program, tentatively named Bay Area Youth Artists for Humanity (BayAFH), is a non-profit arts center which employs Bay Area high school students and practicing artists to produce artwork on commission and for gallery exhibitions. The program is modeled on Artists for Humanity, highly-successful non-profit that began in 1991. The program’s youth artists learn about art by making objects and images that are their own rather than through didactic classroom exercises. The program posits that all its participants are artists, and that the line traditionally drawn between student and teacher will be blurred into a more meaningful relationship between youth artists and mentor artists. The classroom environment will be dissolved into the studio, a flexible workspace that allows artists to express themselves freely. That the studio is the epicenter of learning might seem obvious and be taken for granted by students and professors in a graduate architecture program. However, for high school students who often feel disenfranchised and voiceless within the confines of classroom, the provision of a space in which they can be themselves, learning and making in an environment where they feel comfortable can be life-changing. Understanding the space of the artist at multiple scales of experience is essential to the development of the program and the architecture that which support it.

While the education and empowerment of Oakland’s youth through art-making is the primary goal of this program, this process is impossible without the involvement of dedicated and experienced artists who are willing to share the skills and knowledge with the youth. Mentor artists from diverse fields of practice will be welcomed to the program. The program will provide a personal studio space to each artist in exchange for their service as mentors to the youth studio. Studios will be offered in painting and drawing, photography, sculpture, graphic design, furniture and architecture. Students in all studios will have opportunity to work on both personal projects and group commissioned projects. The mentor’s responsibility is not to tell the youth artist what to make, but to guide them towards the achievement of their vision, providing new methods for making and challenging the youth to constantly expand their abilities and understandings of art. This is a reciprocal relationship. Within this open and egalitarian environment, everyone has something to learn from everyone else around them. There are no tests or exams to determine who is eligible to gain from this program and to evaluate who is better than who. A show of genuine commitment and zeal towards making and learning in this environment is all that is necessary to participate. This program walks the line between art as a medium for social change and art for arts sake. It holds the premise that individual artist has the right and perhaps the duty to express themselves as such, but that the work of the artist is most meaningful when it is part of the shaping of a collective spirit or vision amongst these diverse individuals.

This thesis will propose a design for a permanent home for BayAFH . This will be an epicenter for a larger community that provides physical space for participating artists to come together. This is an architecture at the service of artists, and the design establish a more dynamic and reciprocal relationship between architectural form and arts practice, education and exhibition. In architectural education and practice, program is generally understood as a system of square-footage allotments given over to the particular functions of the building. Formal envelopes are developed into which these functional requirements are slotted in. Given the emphasis on the program and participants, this architectural project will attempt to serve the needs of the participants rather than impose the designer’s conception of what is artistic space. Nevertheless the program suggests a variety of spaces to be composed by the architect, including a large open studio floor, between five and ten individual studios, machine and sculpture workshops, administrative office space, a large gallery that accommodates a variety of art forms and can be used for parties and functions, and a gallery store that provides a direct, commercial outlet for the program’s products.

The open studio floor is the physical and ideological heart of the program. This is where the core relationships between the artists are established. Rather than assigning specific desk spaces to individual students, each youth artist will be provided with a kit of parts to assemble on the open studio floor, allowing them to shape the environment around them and establish amongst themselves the relationships between public and private, individual and collective. This may oftentimes be a contentious process, but learning to work together and share space, material and ideas is a vital part of the artist’s education. For artists involved in the architectural and furniture design studios, projects would often be focused on adding to and improving the building’s spaces and facilities. All of the program’s participants would be included in continual efforts to reconceive the relationship between artists and their space within the framework of the BayAFH facility.

Materials and surfaces will be provided to the program’s youth artists. The styles, subjects, and ideas behind the art will be their own. In return, their work will be exhibited in the gallery space of the arts center and in outside exhibitions arranged by the program. An important part of the learning experience is for these young artists to be involved with the organization, installation and promotion of the gallery exhibitions and openings, so that they engaged not only in the production of art, but also its social and business components. In order to empower Oakland’s youth through art, they must be able to express themselves through both physical artifacts and a social involvement with each other, their mentors, and the community. From personal experience, I can say that what I learned the most from my time at AFH was how to talk to and work with other people that were very different than me. Art is a medium through which people from diverse ages, races, religions, neighborhoods and interests can come together to create, to learn, to teach and to collaborate. Perhaps this vision is naïve and idealistic, given the difficult constraints of our time and place. However, I know from experience that it is possible to achieve, and look forward to both expanding the realm of possibility and finding practical solutions for implementation of the program in the near future.

While the education and empowerment of Oakland’s youth through art-making is the primary goal of this program, this process is impossible without the involvement of dedicated and experienced artists who are willing to share the skills and knowledge with the youth. Mentor artists from diverse fields of practice will be welcomed to the program. The program will provide a personal studio space to each artist in exchange for their service as mentors to the youth studio. Studios will be offered in painting and drawing, photography, sculpture, graphic design, furniture and architecture. Students in all studios will have opportunity to work on both personal projects and group commissioned projects. The mentor’s responsibility is not to tell the youth artist what to make, but to guide them towards the achievement of their vision, providing new methods for making and challenging the youth to constantly expand their abilities and understandings of art. This is a reciprocal relationship. Within this open and egalitarian environment, everyone has something to learn from everyone else around them. There are no tests or exams to determine who is eligible to gain from this program and to evaluate who is better than who. A show of genuine commitment and zeal towards making and learning in this environment is all that is necessary to participate. This program walks the line between art as a medium for social change and art for arts sake. It holds the premise that individual artist has the right and perhaps the duty to express themselves as such, but that the work of the artist is most meaningful when it is part of the shaping of a collective spirit or vision amongst these diverse individuals.

This thesis will propose a design for a permanent home for BayAFH . This will be an epicenter for a larger community that provides physical space for participating artists to come together. This is an architecture at the service of artists, and the design establish a more dynamic and reciprocal relationship between architectural form and arts practice, education and exhibition. In architectural education and practice, program is generally understood as a system of square-footage allotments given over to the particular functions of the building. Formal envelopes are developed into which these functional requirements are slotted in. Given the emphasis on the program and participants, this architectural project will attempt to serve the needs of the participants rather than impose the designer’s conception of what is artistic space. Nevertheless the program suggests a variety of spaces to be composed by the architect, including a large open studio floor, between five and ten individual studios, machine and sculpture workshops, administrative office space, a large gallery that accommodates a variety of art forms and can be used for parties and functions, and a gallery store that provides a direct, commercial outlet for the program’s products.

The open studio floor is the physical and ideological heart of the program. This is where the core relationships between the artists are established. Rather than assigning specific desk spaces to individual students, each youth artist will be provided with a kit of parts to assemble on the open studio floor, allowing them to shape the environment around them and establish amongst themselves the relationships between public and private, individual and collective. This may oftentimes be a contentious process, but learning to work together and share space, material and ideas is a vital part of the artist’s education. For artists involved in the architectural and furniture design studios, projects would often be focused on adding to and improving the building’s spaces and facilities. All of the program’s participants would be included in continual efforts to reconceive the relationship between artists and their space within the framework of the BayAFH facility.

Materials and surfaces will be provided to the program’s youth artists. The styles, subjects, and ideas behind the art will be their own. In return, their work will be exhibited in the gallery space of the arts center and in outside exhibitions arranged by the program. An important part of the learning experience is for these young artists to be involved with the organization, installation and promotion of the gallery exhibitions and openings, so that they engaged not only in the production of art, but also its social and business components. In order to empower Oakland’s youth through art, they must be able to express themselves through both physical artifacts and a social involvement with each other, their mentors, and the community. From personal experience, I can say that what I learned the most from my time at AFH was how to talk to and work with other people that were very different than me. Art is a medium through which people from diverse ages, races, religions, neighborhoods and interests can come together to create, to learn, to teach and to collaborate. Perhaps this vision is naïve and idealistic, given the difficult constraints of our time and place. However, I know from experience that it is possible to achieve, and look forward to both expanding the realm of possibility and finding practical solutions for implementation of the program in the near future.

Labels: dbackman

11.14.2006

11.07.2006

Those crazy artists are taking over Oakland!

From the Crucible's Annual Fire Arts Festival

Held in a large open parking lot at 7th & Union next to where the BART emerges from the tangle of the 980 freeway. The lot is publicly owned and is used as overflow parking for the West Oakland BART. These swaths of parking that straddle the large pieces of infrastructure are some of the last open building sites in West or Downtown Oakland. Located across the street from the Crucible, another arts center in this area could solidify the transformative value of the arts for this area, which the city has already designated for community oriented development. Rather than compete, the two arts program can compliment eachother, with the Crucible offering industrial arts courses and facilities and the new program focusing on art and architecture. The massive brutal cuts of these freeways once tore this nieghborhood apart, quickly speeding commuters through the area while cutting it off from the heart of the city. This program could not only make the immediate area a more beautiful, dynamic space, but also reconnect it back to the city.

Labels: dbackman

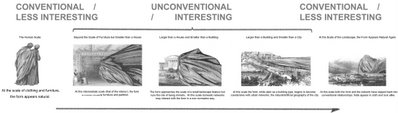

Diagram Deployment

Using the same diagram at different scales can produce drastically different effects. Diagrams considered conventional at the large end of the spectrum--the scale of the city or the neighborhood--or at the small end--the scale of clothing--are regarded as radical at the middle scales of architecture. They resist traditional architectural arrangement and tectonics at these scales. These territorial infringements on scale are among the most difficult to operate well within, but they can be most rewarding when successfully negotiated. --Reiser and Umemoto

Using the same diagram at different scales can produce drastically different effects. Diagrams considered conventional at the large end of the spectrum--the scale of the city or the neighborhood--or at the small end--the scale of clothing--are regarded as radical at the middle scales of architecture. They resist traditional architectural arrangement and tectonics at these scales. These territorial infringements on scale are among the most difficult to operate well within, but they can be most rewarding when successfully negotiated. --Reiser and Umemoto

11.06.2006

What's next?

Thus far I've been visiting two classes twice a week and helping them solve issues with the perspective drawings they are creating. Time is short (and often wasted) and it is difficult to get some students to remain engaged with their work for the duration of the period. Others are more focused but shy and hesitant to ask for help. As this project comes to a close I am struggling to find a way to introduce another, more design oriented project (although there are a fair amount of design issues inherent to the work they are already producing). I keep wondering, " are they just too young to have a serious interest in architecture?" Then again, Le Corbusier could not have been much older than these students when he designed his first house, not that a mind like Corbu's is to be found in every randomly selected portion of the population. Julia Morgan passed through the same hallowed halls of Oakland High and left with enough certainty of purpose to demand admission into L'ecole des Beaux-arts despite their expressed policies of gender-discrimination. So how does one get students to engage critically with the built environment; to make observations and question the validity of existing design solutions? Mark suggested a film, which I think is a great process, but one that requires as much vision and planning as architecture itself in a medium in which I have little experience. Photography may be another method of engagement. Perhaps I could give the students disposable cameras and ask them to photograph observations they make about their environment. Any suggestions?

Thus far I've been visiting two classes twice a week and helping them solve issues with the perspective drawings they are creating. Time is short (and often wasted) and it is difficult to get some students to remain engaged with their work for the duration of the period. Others are more focused but shy and hesitant to ask for help. As this project comes to a close I am struggling to find a way to introduce another, more design oriented project (although there are a fair amount of design issues inherent to the work they are already producing). I keep wondering, " are they just too young to have a serious interest in architecture?" Then again, Le Corbusier could not have been much older than these students when he designed his first house, not that a mind like Corbu's is to be found in every randomly selected portion of the population. Julia Morgan passed through the same hallowed halls of Oakland High and left with enough certainty of purpose to demand admission into L'ecole des Beaux-arts despite their expressed policies of gender-discrimination. So how does one get students to engage critically with the built environment; to make observations and question the validity of existing design solutions? Mark suggested a film, which I think is a great process, but one that requires as much vision and planning as architecture itself in a medium in which I have little experience. Photography may be another method of engagement. Perhaps I could give the students disposable cameras and ask them to photograph observations they make about their environment. Any suggestions?